Oak Hill Country Club Golf Tournaments

1949 U.S. Amateur

Joseph Dey, the Executive Director of the United States Golf Association, couldn’t believe his eyes when he visited Oak Hill in 1948 to see if the East Course was worthy of hosting the 1949 U.S. Amateur.

"Where have you been for 20 years?” Dey asked rhetorically. “There's nothing like this in the whole country.”

Needless to say, Dey and his USGA brethren happily marched into Rochester the following summer, and following renowned amateur Charlie Coe’s 11-and-10 championship match rout of Rufus King, USGA President Fielding Wallace said "It is my considered opinion that this was one of the most successful, interesting and exciting tournaments ever held."

And so it began, Oak Hill’s unrelenting status - which continues to this day - as one of the most respected and cherished facilities in American golf.

Coe had little resistance in winning his first three matches, then had to go a combined 40 holes in one day to win two matches to reach the semifinals. And then he caught fire again and rolled past Bill Campbell 8-and-7 before inflicting on King the most one-sided championship match defeat in the history of the Amateur.

Charlie Coe, receiving congratulations from revered Oak Hill member Dr. John R. Williams, fashioned one of the most impressive amateur golfing careers in history. Coe won the 1949 Amateur at Oak Hill and the 1958 Amateur at Olympic Club, and lost the 1959 final to Jack Nicklaus. He was a six-time member of the U.S. Walker Cup team, and he established amateur records at the Masters for most starts (19), cuts made (15) and low amateur honors (6) that will likely never be broken. "That's the way I try to look when I swing,” sweet-swinging Byron Nelson once said of Coe’s fluid, effortless motion.

The four men who reached the semifinals of the 1949 U.S. Amateur were, from left, Charlie Coe, Rufus King, future World Golf Hall of Fame inductee Bill Campbell and two-time Amateur champion Willie Turnesa. Others in the field included future Hall of Fame inductees Julius Boros and Joe Carr, and future major tournament winners Dow Finsterwald and Gay Brewer. There was also a 19-year-old kid from Latrobe, Pa. named Arnold Palmer, who lost in the third round to Crawford Rainwater by 4-and-3. Rainwater went on to become a USGA committee man who served as a rules official at the 1989 Open at Oak Hill. Palmer went on to become the King.

1956 U.S. Open

It was unfortunate for Cary Middlecoff that the man chasing him for the 1956 U.S. Open championship was Ben Hogan.

Had it been anyone other than Hogan - who by the time he returned to Oak Hill for the East Course’s inaugural hosting of a professional major championship had become a living legend - Middlecoff would have dominated the headlines for the way he expertly negotiated a demanding layout that did not yield a single under-par 72-hole total, including his own.

But unfair as it may be, what is remembered most from that exciting tournament when Oak Hill flexed its muscles for all the world to see was not that Middlecoff won, but that Hogan lost, his quest for a record fifth U.S. Open title stymied by his miss of a 30-inch putt on the 71st hole.

Middlecoff, who began the fourth round clinging to a one-stroke lead over Hogan, finished an hour before Hogan and was sitting in the locker room watching on television as player after player failed to match his score of 1-over-par 281. Hogan came to the difficult 17th tied with Middlecoff for the lead, but he tapped his par putt just a bit too hard and it took a peak at the cup and kept going.

“It hit the hole and stayed out," Middlecoff said. "I appreciated that.”

Hogan failed to make a tying birdie at 18, and when the last challenger, Julius Boros, was unable to find one more birdie, Middlecoff celebrated the 37th victory of his career, one in which he never broke par-70 in any of the four rounds, prompting him to say “Nobody wins the Open. It wins you.”

Years after his victory at Oak Hill, World Golf Hall of Fame member Cary Middlecoff, who counted two Opens and one Masters among his 40 career victories, recalled the final stroke he made that week when he captured his second U.S. Open title. "I would say that was the greatest accomplishment I ever had on one particular, very important shot," Middlecoff said of the slippery four-foot slider he made for par at the 18th hole that ultimately clinched the championship. "That was the big shot of the tournament for me. I knew I was going to win if I could make it.”

It became apparent in the 1956 Open that the par-5 13th hole was going to become the East Course’s signature tournament hole because of the natural amphitheater that surrounded the green. Here, Bob Rosburg, known now as an accomplished golf analyst, chips to the green as a large gallery looks on.

Ben Hogan, who had one victory and a pair of runner-up finishes in the three tournament appearances he made at Oak Hill, takes a seat behind the 12th tee. In the distance is the recognizable leaning tree along the right side of the fairway.

1968 U.S. Open

Oak Hill played a starring role in the birth of a golfing legend when Lee Trevino - heretofore just another nameless touring pro - launched his Hall of Fame career by making the ’68 Open his first PGA Tour victory.

Trevino came to Oak Hill with about 20 bucks in his pocket and a garment bag with three shirts and three pairs of slacks, then became the first player in history to post four sub-70 rounds in an Open championship. His 5-under-par 275 tied the Open scoring record set a year earlier by Jack Nicklaus, the same Nicklaus who fired up a warning shot the day before the tournament began when he said “Lee Trevino could win this tournament.”

Trevino opened with a 69, and said he’d “love to shoot three more of those.” Well, he managed two more, and threw in a second-round 68 for good measure to outdistance Nicklaus by a comfortable four-stroke margin.

Well, maybe not that comfortable. “I was so nervous I couldn’t get my shots airborne,” the Merry Mex recalled years later. “If you look at the tape all my shots were line drives I was choking so bad.”

Trevino and Bert Yancey battled for the lead for three days, yet no one in Rochester paid much attention to Trevino and he remembered sitting in a golf cart one night drinking a beer and not once being asked for an autograph.

But during the fourth round, the world found out who Trevino was, and no one has stopped asking for his signature since. That day, Yancey skied to a 76 and while Nicklaus made a charge with a 67, it wasn’t nearly enough to catch Trevino.

And if you think hoisting the Open trophy was exciting, that was nothing compared to what happened in the scorers’ tent at the conclusion of the tournament.

“The highlight of that week was meeting Arnold Palmer for the first time,” Trevino said. “I was sitting there signing my card and he came over, shook my hand, and said ‘Nice going, young man.’ Man, that was something.”

Between the 1956 and 1968 U.S. Opens at Oak Hill, Arnold Palmer became the most popular golfer in the world. His galleries were enormous wherever he played, and that was certainly the case at the East Course’s 13th hole even though he was never in contention during the ’68 tournament, finishing 59th. He was even being spied on by the Goodyear blimp off in the distance.

Hord Hardin, who at this time was the President of the USGA before going on to become the chairman of Augusta National, presents the Open trophy to Lee Trevino. It was the Merry Mex’s first of 29 victories on the PGA Tour. “It was an unforgettable week for me," Trevino said. "Rochester will always have a special place in my memory.’’

Twenty-one years after winning the Times-Union Open, Sam Snead played at Oak Hill for the final time in the ’68 Open. Trying to complete the career grand slam, the 56-year-old shot 68 in the fourth round and finished ninth. When told that he shot a 67 in the final round of the T-U Open, Snead remarked “I must be slipping.”

Golf on television has come a long way from its primitive roots in the 1950s. At the ’68 Open, ABC was the host network, and here is one of the trucks that was on hand at Oak Hill. The broadcasters for the event were, from left, Jim McKay, Bill Fleming, Byron Nelson and Chris Schenkel.

1980 PGA Championship

Jack Nicklaus had dominated the world of golf for more than 15 years, but in the late 1970s, the Golden Bear was being called the Olden Bear because his winning ways had abated.

As Nicklaus kicked off the 1980 PGA Tour season, he was turning 40 years old, and he had been supplanted by Tom Watson as the world’s No. 1 player. “But that didn't eliminate my feeling that I could come back,” said Nicklaus, who did exactly that, winning the U.S. Open at Baltusrol with a record-setting score of 272, and then capturing the 17th professional major championship and 71st overall PGA Tour victory of his illustrious career by lapping the field in the PGA Championship at Oak Hill.

Nicklaus, who became just the third player in history to win the Open and PGA in the same year, was superb during his four tours of the newly-renovated East Course. He opened 70-69 to trail Gil Morgan by a shot, then dusted the competition with a spectacular third-round 66.

The three-stroke lead he began the fourth round with may not have seemed like much, but in closing with a classy 69, one of only three players to break par-70 that day, he was a PGA-record seven shots ahead of runner-up Andy Bean, his 274 total the lowest ever posted at Oak Hill.

"I played as fine a finishing round in a major as I've ever played," said Nicklaus, who tied the record of Rochester native Walter Hagen – for whom the tournament was dedicated to – with his fifth PGA Championship victory. "Oak Hill is a marvelous golf course, one of the top 10 or 12 true championship courses.’’

Oak Hill had hosted successful U.S. Opens in 1956 and 1968, but when the USGA turned down its request to bring the event back in the late 1970s, club officials sprang into action. The USGA intimated that the East Course had become antiquated, and a renovation was necessary before it would consider returning. Noted architect George Fazio and his rising star nephew, Tom, were hired, and they built new par-3 holes at Nos. 6 and 15, and re-designed the fifth and 18th holes, which brought the course back up to major championship standards. It was put on display for the first time during the 1980 PGA Championship, and Jack Nicklaus was the only player to break par for the week.

1984 U.S. Senior Open

Once again, it was a faulty stroke on a putting green by a historic figure that overshadowed an Oak Hill victory by a solid but not quite as popular champion.

Much like Cary Middlecoff had benefited from Ben Hogan’s miss from 30 inches in the 1956 U.S. Open, Miller Barber’s path to victory in the first Senior event held on the East Course was cleared in part by Arnold Palmer’s inexplicable whiff of a tap-in at the 15th hole in the final round.

“I didn't see him miss that putt," said Barber, and the gallery surrounding the hole could say the same thing. But Palmer knew what he had done, and no one should have been surprised that the King did the honorable thing and called the penalty on himself.

Barber, who won 11 PGA Tour events before enjoying tremendous success on the Senior Tour, had begun the final round one shot behind the iconic Palmer, but Barber had gone ahead with a series of 10 straight pars and as they stood on the 15th green, Barber was now ahead by two shots.

Palmer had air-mailed a 7-iron over the green at the par-3, chipped to 10 feet, and missed his par-saving putt, leaving it just on the edge of the cup. He walked up and nonchalantly stabbed at it, but he stubbed his putter and never touched the ball. After sweeping it in on the second try he immediately informed Barber that his score was a double-bogey 5.

"I couldn't believe it,” said Barber, who was so thrown by the incident that he went on to three-putt for a bogey, though his lead still increased to three shots. “In my wildest imagination I wouldn't have known he had done it if he hadn't spoken up.’’

Palmer birdied 16, and Barber drove into trouble at 17 and Arnie’s Army surged with excitement, but Barber hit a brilliant recovery shot, saved par, and made a routine par at 18 to wrap up the victory.

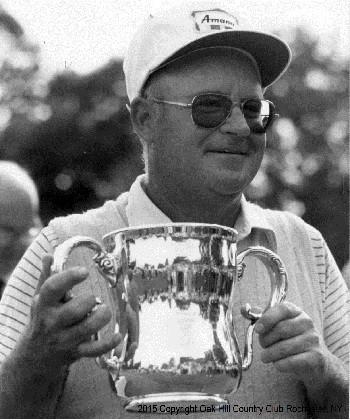

Miller Barber did not count any major titles among his 11 PGA Tour victories, but he went on to enjoy one of the most successful Senior Tour careers in history as he won 24 times, five of the victories coming in senior majors. Starting in 1982 he won one Senior major in four straight years including three U.S. Senior Opens.

One of the key moments of the 1984 U.S. Senior Open occurred on the 15th tee in the final round. Arnold Palmer and his caddie, Creamy Carolan, disagreed on what club to hit at the par-3. Palmer ceded to Carolan, hit a 7-iron instead of the 8 that he preferred, and knocked his shot over the green. Ultimately, he three-putted for a double bogey which foiled his chances of catching Miller Barber.

1989 U.S. Open

After a 21-year hiatus, the USGA brought its premier event back to Oak Hill, and as it always had, the East Course held up fabulously as Curtis Strange’s winning score of 278 was higher than Nicklaus’s 274 in the 1980 PGA and Trevino’s 275 in the 1968 Open.

For Strange, it was a historic Sunday in the blazing June sun as he became the first man since Ben Hogan in 1951 to win back-to-back Opens. Strange followed up his triumph at Brookline in 1988 with a marvelously steady final-round 70 that featured 15 straight pars, a clutch birdie at No. 16, and a bogey at 18 when he safely three-putted in order to protect a two-shot lead.

“Move over, Ben,” Strange announced in the press tent afterward. "It's not so much what Hogan did. It's what others have not done. The great Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus and Tom Watson have not won back-to-back Opens.”

And no one has done it since.

The week began with an Open-record 21 players breaking par-70 led by the matching 66s recorded by Payne Stewart, Bernhard Langer and Jay Don Blake, but Strange leaped into the lead with a brilliant second-round 64 that matched the East Course’s competitive record set by Hogan in the 1942 Times-Union Open.

Strange and Kite played side-by-side on a soggy, rain-delayed Saturday and Kite was the undeniable winner, shooting 69 to Strange’s 73. But on Sunday, Kite made a disastrous triple-bogey at the difficult 406-yard fifth hole and never recovered. While he continued his meltdown with bogeys at Nos. 8 and 10 and double bogeys at 13 and 15, Strange was playing mistake-free and beating back all challengers.

When he rolled in a 10-footer for birdie at No. 16, it gave him just enough of a cushion to hold off Chip Beck, Mark McCumber and Ian Woosnam over the final two holes to secure what became, rather remarkably considering his stature in the game at the time, the 17th and final PGA Tour victory of his career.

Hometown hero, Oak Hill member, and 1988 PGA champion Jeff Sluman played for the first time in an Oak Hill major championship, but he was unable to display the full range of his game because six weeks before the tournament he underwent an emergency appendectomy. Sluman, in a star-power threesome that included past Oak Hill major winners Jack Nicklaus and Lee Trevino, struggled to rounds of 75-71 and missed the cut. “I can look myself in the eye and say I did the best I could," Sluman said. “But considering what happened to me health-wise, I think I'm fortunate just to have been able to play.”

Tom Kite had already established himself as a world-class player when he arrived at Oak Hill for the ’89 Open, but the one blight on his resume was the absence of a major championship. When Kite took a three-shot lead to the fifth tee on the final day, it was looking as if his long-awaited coronation was going to take place a few hours hence. Instead, he pushed his drive into Allen’s Creek, went on to score a triple-bogey 7, and imploded from there, shooting a 78 to tie for ninth. He did go on to win the 1992 Open at Pebble Beach.

One of the most amazing feats in the history of golf occurred in the early-morning hours of the second round when, in a two-hour span, Doug Weaver, Mark Wiebe, Jerry Pate and Nick Price aced the 167-yard sixth hole. “Unusual, exciting, historic – any of those words sum it up,” said Pate. Later in the day, Fred Funk made a birdie-2, turned to the gallery and said “I can’t believe you’re clapping for a birdie.”

1995 Ryder Cup

In recent years Europe has dominated the Ryder Cup Matches, and you can trace the turning of the tide back to a never-to-be-forgotten September Sunday afternoon in 1995 with Oak Hill – Heartbreak Hill as it was labeled, at least for the Americans - serving as the landscape.

From 1927, when English seed merchant Samuel Ryder donated the small trophy named in his honor that is now one of the most-coveted pieces of hardware in sports, into the mid-1980s, the Ryder Cup had resided almost exclusively on this side of the Atlantic Ocean as the United States won the biennial competition 21 of the first 25 times it was contested.

But Europe ended a 28-year drought by winning in 1985, then continued to close the gap in the next decade, so by the time the Matches came to the East Course, the sides were virtually even.

On the first day, played in cold, rainy, downright miserable weather that should have favored Europe, the U.S. opened a 5-3 lead, and the Americans were still ahead 9-7 as the second day came to a dramatic conclusion when Corey Pavin chipped in for a winning birdie that produced a roar so loud it would have drowned out the Concorde had it flown over the course at that moment instead of its first pass earlier in the week.

Heading into their strongest segment, the Sunday singles, the U.S. appeared poised to retain the Cup it had recaptured in 1991 and defended in 1993. Instead, the Europeans shocked the world by winning seven matches, losing four and tying one to produce a 14 ½ to 13 ½ victory, and the Ryder Cup has never been the same as Europe has won five of the last six.

Oak Hill honored the European team with a tree on the Hill of Fame and the plaque affixed to the tree sums up their accomplishment: “Their magnificent comeback victory is in the first rank of the most stirring triumphs in the history of golf and reminds us, once again, why golf is the best of games.”

One of the controversial issues of the 1995 Ryder Cup was U.S. captain Lanny Wadkins’ selection of Curtis Strange as one of his captains’ picks. Strange had not won a tournament since his victory in the 1989 U.S. Open at Oak Hill, and while recognizing that, Wadkins pointed to Strange’s previous success on the East Course as one of the reasons he selected him. Alas, Nick Faldo won the final three holes of his critical singles match with Strange which ultimately turned the matches in Europe’s favor.

During Saturday morning’s alternate shot play, Italy’s ebullient Costantino Rocca aced the sixth hole as he and Sam Torrance drummed Davis Love III and Jeff Maggert by 6-and-5. “It’s hard to lose the hole with a one,” Rocca said in his halted English.” It was just the third hole-in-one in the history of the Ryder Cup, and the next day, during the singles, came the fourth when Englishman Howard Clark dunked his tee shot at the 11th hole on his way to defeating Peter Jacobsen.

European captain Bernard Gallacher had presided over two losing Ryder Cup teams, but in his final year at the helm, his players responded with a stirring victory on the foreign soil of Oak Hill. Of the European press who were predicting an American runaway victory, Gallacher said “They got it wrong.’’

1998 U.S. Amateur

In many ways Oak Hill came full circle in 1998. Nearly a half century after making its major tournament debut by hosting the 1949 U.S. Amateur, the USGA brought the event back to the venerable East Course – and, for the first time in competition, the West Course - for another rousing week of golf in its purest form.

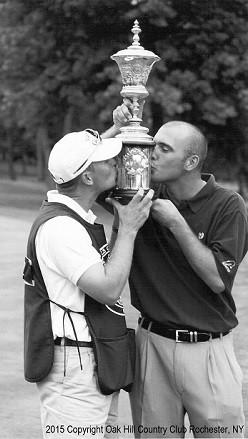

And just as it had in every championship it had hosted to this point, Oak Hill produced a worthy, big-name champion. This time it was long-hitting Hank Kuehne - who soon thereafter would take his game to the PGA Tour – smashing his way to victory over gritty, then-career amateur Tom McKnight who has since joined the pay-for-play set and become a successful competitor on the Champions Tour.

Following two-plus days of qualifying and three rounds of match play, the tournament really heated up with some delicious quarterfinal matches as Sergio Garcia eliminated defending Amateur champion Matt Kuchar while Kuehne whipped Bryce Molder and McKnight and Bill Lunde also advanced. When Kuehne and McKnight survived their semifinal tests, it set up a 36-hole final between two good friends who were about 20 years apart in age.

Kuehne opened a 3-up lead after the first 18, and after McKnight rallied to go 1-up through six holes in the afternoon, Kuehne made his move by winning four of the next five holes and ultimately won 2-and-1.

Oak Hill’s hosting of the Amateur turned the event into one of the biggest successes in the tournament’s history. As usual, Rochester’s knowledgeable golf fans flocked to the course and produced galleries rarely seen at the Amateur and none was larger than the turnout for the Friday quarterfinals when the featured match pitted reigning U.S. Amateur champion Matt Kuchar against reigning British Amateur champ, and future PGA Tour star, Sergio Garcia. The two players trudged around the East Course with about 10,000 fans in tow, and they provided a scintillating display of shot-making before Garcia prevailed 2-and-1.

Every U.S. Amateur features a number of players who go on to compete as professionals, many on the PGA Tour. At Oak Hill in 1998, the list included eventual champion Hank Kuehne, Sergio Garcia, Aaron Baddeley, Adam Scott, Charles Howell III, Bryce Molder, Matt Kuchar, J.J. Henry, Ben Curtis, Hunter Haas, David Eger and Tom McKnight.

The day before the 36-hole stroke-play qualifier began, good friends Hank Kuehne and Tom McKnight played a late-afternoon practice round together, during which McKnight quipped "Wouldn't it be great if we can meet each other in the finals?" A week later, that’s exactly what they did.

For the first time in a major tournament the West Course was utilized during the ’98 Amateur. With 312 players in the starting field, both courses were needed for the 36-hole stroke-play qualifying. Unlike its more famous big brother to the East, the West Course remains very true to Donald Ross’ original design concepts, and it held up just fine. Playing to a par of 69, the average qualifying score was 5.34 over par while it was 5.89 over par on the East.

2003 PGA Championship

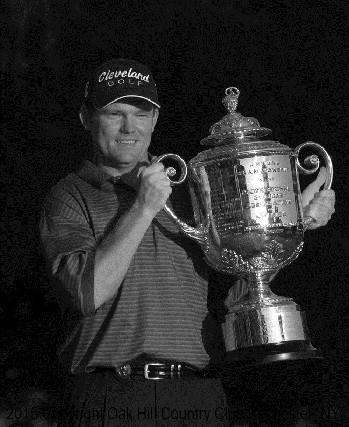

No one knew who Shaun Micheel was when he showed up at Oak Hill to play in the PGA Championship. By the end of the week he was the toast of the golf world, and the author of one of the greatest clutch shots ever struck in a major championship.

Micheel, the definition of the nondescript touring pro, a 34-year-old who hadn’t won in his first 164 PGA Tour starts, came to the 72nd hole clinging to a precarious one-stroke lead, and when he drove into the left rough, there was a sense that the magnitude of the moment was going to engulf him.

Instead, his caddie told him the yardage was 175 yards to the pin, handed him a 7-iron, and watched with the rest of the world as Micheel launched a perfect shot that stopped two inches from the hole, securing Micheel’s victory which meant Oak Hill had now been the place where two major winners – Micheel and Lee Trevino – had earned their first victories.

Micheel, who in a unique twist graduated from the same high school in Memphis as Cary Middlecoff, winner of the 1956 Open at Oak Hill, said “I can't really believe that this happened to me.”

Neither could anyone else.

He and Chad Campbell came down to the final hole and those who were seated in the packed grandstand in that majestic setting around the 18th green witnessed Micheel’s shot for the ages. “That would probably be the best shot I've seen under pressure," said Campbell.

His name isn’t Snead, Hogan, Trevino or Nicklaus, but no one that week – not Woods, Mickelson, Ernie Els or Vijay Singh - was better than Micheel’s 4-under 276, and thus, he is deserving of his place in Oak Hill’s illustrious history.

For the first time since 1998, Tiger Woods went without a victory in the major championships in 2003. His last chance to break the “drought” came at Oak Hill, but for just the third time in his career he played all four rounds of a major over par and was never a factor. His 12-over total of 292 remains the worst four-round score of his career in a major. "It was a tough week," he said. "I fought hard just to shoot bad."

At the 2003 PGA, 96 of the top 100 ranked players in the world teed it up at Oak Hill, and only two – Chad Campbell and Tim Clark – managed to break par for the week. World No. 1 Tiger Woods said Oak Hill was the “hardest, fairest golf course we’ve ever played” and who could argue. He tied for 39th, Ernie Els tied for fifth, Phil Mickelson tied for 23rd and Vijay Singh tied for 34th.

2008 Senior PGA Championship

For more than a decade Jay Haas had been using his admittedly disappointing performance in the 1995 Ryder Cup Matches at Oak Hill as an inspirational tool to push himself to future greatness.

He never forgot the wayward tee shot he struck on the 18th hole of his singles match with Europe’s Philip Walton, a swing that doomed him and helped secure the United States’ defeat. Haas vowed that someday he would turn that experience into a positive.

Clinging to a one-shot lead over Bernhard Langer as he strode to the final hole of the 69th Senior PGA Championship, Haas thought back to 1995 and said to himself, “Well, you've been talking about this, so it's time to put up or shut up.” A solid par secured the victory for Haas, his second Senior PGA win in the last 3 years.

On a course that proved to be a brutally difficult test for the world’s finest 50-and-over golfers, Haas posted a 7-over-par total of 287—highest ever in a 72-hole major event at Oak Hill—to edge Langer by a stroke. -by Sal Maiorana

https://www.oakhillcc.com/files/PGA_Special_Edition.pdf

2013 PGA Championship

Jason Dufner didn't last long when he competed in the 1998 U.S. Amateur at Oak Hill. He qualified for match play, but was eliminated in the second round. Still, Dufner loved the East Course and really thought it fit his game, so when he returned 15 years later to play in the 2013 PGA Championship, he had a good feeling about the week.

"Guys tend to like golf courses that suit their games, and even then I felt like this place suited my game," he recalled of his experience at the Amateur. Turned out he was right. Dufner set a new 72-hole East Course stroke-play record with a 10-under 270 to edge Jim Furyk by two shots for his first major championship victory. Furyk at 272, and Henrik Stenson at 273, also bested Jack Nicklaus' 274 that had stood as the standard since the 1980 PGA.

Dufner electrified the huge galleries with a second-round 63 that set a new course record, wiping out the matching 64s shot by Ben Hogan (1942 Times-Union Open) and Curtis Strange (1989 U.S. Open). He missed a 12-foot birdie putt at No. 18 that would have given him the lowest score ever recorded in major championship history. "I know the history of major championships so I knew that nobody had shot 62, and the course record I had heard on TV earlier in the week," said Dufner. "So I knew where I stood and you couldn't have a better chance at history on the last hole. I wish I had that putt back again."

Furyk's third-round 68 gave him a one-shot lead on Dufner heading into the final round, but Dufner regained the lead after back-to-back birdies at Nos. 4 and 5. A Furyk birdie at No. 6 left both players at 10-under, but Dufner's birdie at eight, and Furyk's bogey at nine proved the difference as they produced identical scorecards over the final nine holes, each parring the first six, birdieing the 16th, and bogeying the 17th and 18th.

Thus, Dufner became part of Oak Hill lore, and he certainly appreciated what that meant. "They are very knowledgeable about their golf and the history of the game goes way back here in Rochester and it's great to be part of that," he said. -by Sal Maiorana

2013 PGA Championship Quercus

http://www.pga.com/pgachampionship/2013

2019 KitchenAid Senior PGA Championship

Ken Tanigawa would come from literally nowhere to win the 2019 KitchenAid Senior PGA Championship at Oak Hill.

After graduating from UCLA, Tanigawa turned professional in 1990 but after more than a decade of disappointments on the Ben Hogan Tour (now The Korn Ferry Tour) and the Japan Golf Tour he decided to return to amateur status. But hope springs eternal and with several strong wins, he enters Q-School as an amateur and qualifies for the 2018 Champions Tour. He would win the PURE Insurance Championship in late September 2018 and be named 2018 PGA Champions Rookie of the Year.

A virtual unknown when Tanigawa arrived at Oak Hill he would face some great senior players including Retief Goosen, Bernhard Langer, Steve Stricker, Darren Clark and a host of the very best. Tanigawa came from three strokes behind in the final round and would card a 72-hole score of -3 to hold off a charge by Scott McCarron, his UCLA golf teammate, whose putt to tie on the 72nd just slid by the hole to finish -2. Defending champion Paul Broadhurst who had played bogey-free through the first three days would struggle on the back nine on Sunday with a double bogey on the 16th hole to fall two back of Tanigawa going into the final two holes and finish at -1. - by Fred Beltz, Oak Hill Historian.